Article published originally at |

Haunting Beauty

Dean Mitchell paints deeply personal visions of life’s fragile side

by Norman Kolpas

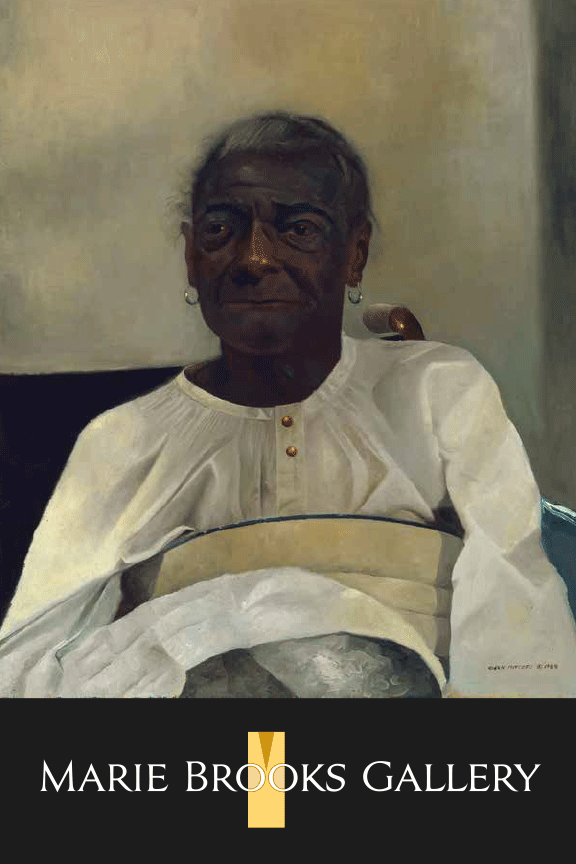

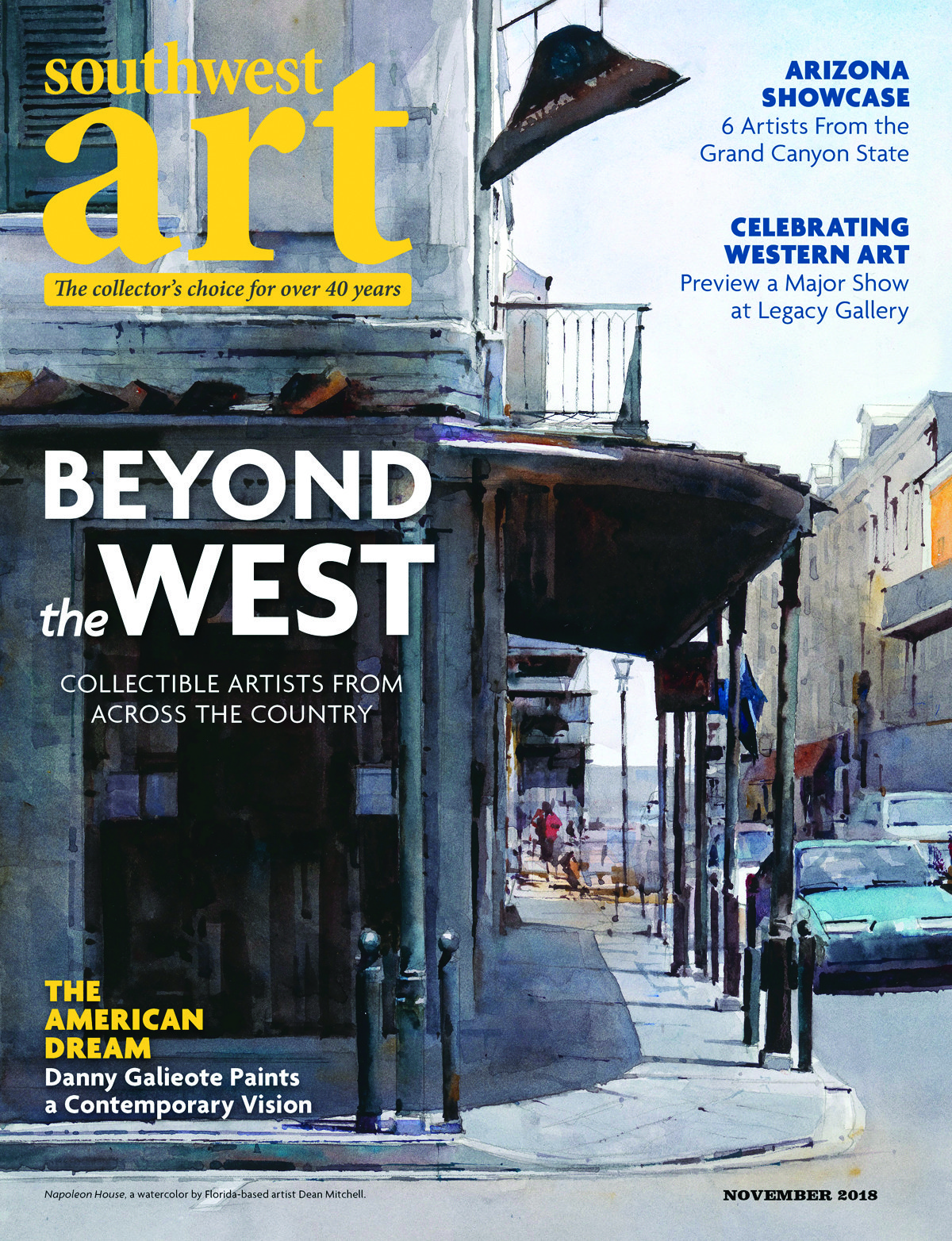

Tumbledown homes in barren landscapes, vibrantly lit by the blazing sun. Inner-city streets, their old buildings worn yet elegant. Humble, hardworking people, their gazes relentless, their faces quietly proud. Such is the world as Dean Mitchell sees it. “I paint the human condition—desolation and hardship,” he states matter-of-factly. His compositions are arresting and his works impeccably executed, some in watercolor and others in oil or acrylic. “I am drawn to anything that is overlooked or felt to be ugly or discarded, because there’s a haunting quality, a power, and a beauty to it.”

Mitchell uncovers and portrays the innate beauty of his subjects so deftly and powerfully, in fact, that a critic writing in the New York Times was moved to describe him as “a virtual modern-day Vermeer of ordinary black people given dignity through the eloquence of his concentration and touch.” Another writer, covering a show of Mitchell’s work for the Hartford Courant, dubbed him “an assured artist whose mature style merits favorable comparison to the likes of Andrew Wyeth and Edward Hopper.”

Flattering though it is to point out such similarities of style, Mitchell’s art stands securely on its own. Having lived a dramatic personal journey of his own, the 62-year-old artist possesses a formidable talent that needs no comparison.

“You can’t make a living as a black man painting pictures. That’s white-people stuff.” Those were the words Mitchell’s mother spoke to him when he told her, during high school, that he hoped to go on to study art.

- Dean Mitchell, Isolation, acrylic, 17 x 17.

- Dean Mitchell, Gordon, oil, 30 x 40.

- Dean Mitchell, Dry Rot, acrylic, 20 x 30.

- Dean Mitchell, Maricopa County House, oil, 24 x 36.

- Dean Mitchell, Napoleon House, watercolor, 15 x 11.

- Dean Mitchell, Florida Cypress, watercolor, 15 x 10.

Mitchell had been conceived during an affair his mother had while a college student. “She fled our small town of Quincy, FL, and gave birth to me in Pittsburgh,” Mitchell recounts. When he was 11 months old, his mother visited home and, not knowing that her brother had tipped off their parents, was greeted by her own mother with the words, “Where’s the child? Bring him home.”

Mitchell’s grandmother raised him in Quincy, first in a humble dwelling that was “almost like a slave shack of a house, with nails sticking through the boards.” After his grandfather died of a heart attack a few years later, a life-insurance policy made it possible for them to move to a less rickety home in the same town.

Mitchell’s talent first showed itself when he was about 5 years old. “My grandmother bought a paint-by-numbers set for me,” he remembers. “I did the first one following all the numbers. The next one, I painted freehand.”

A love of drawing took hold in him. On Saturday mornings, he’d sit in front of the TV watching cartoons and faithfully rendering Mickey Mouse, Mighty Mouse, and other cartoon characters in pencil on paper. Eventually, he progressed to live subjects: “When I was 10 or 11, my uncle would sit in this green reclining chair and fall asleep after a day’s work, and I would draw him and then do his portrait with these little tubes of oil paint I had.”

His skills, and his dedication to art, progressed through junior and senior high, which included a three-year family sojourn in Philadelphia from 6th to 9th grades. “Instead of eating lunch, I would keep my money so I could buy art books,” he remembers. He drew his own pictures to illustrate reports, and his talent even began to win him his first commissions. One neighbor asked him to paint two murals for her children’s rooms, paying him $10 apiece. Another forked over $25 for a scene featuring Mitchell’s original cartoon characters painted on a fence.

Back in Quincy at Carter-Parramore High School, he continued to find fulfillment in his artistic talent. That led, in turn, to his decision to apply to art school—and the declaration by his mother, whom he “maybe saw once a year,” that art was not a wise career choice for a young black man.

- Dean Mitchell, Code Red, acrylic, 11 x 17.

- Dean Mitchell, Butter Dish, Spoon, & Tea, acrylic, 8 x 7.

- Dean Mitchell, Broken Wealth, oil, 19 x 20.

- Dean Mitchell, Bob Ragland, acrylic, 10 x 8.

- Dean Mitchell, Ybor Corner, acrylic, 15 x 10.

- Dean Mitchell, Windows & Doors, acrylic, 10 x 8.

Nonetheless, he applied and was accepted to Ohio’s Columbus College of Art & Design on a work-study scholarship. He found the transition difficult. “I was kind of a small-town kid. It was a tough, frustrating time for me trying to figure it out. I lost almost 60 pounds from the stress and almost dropped out. When I went home for Christmas, my grandmother said, ‘That boy can’t go back. He’s as thin as a rail and just looks ill.’” But Mitchell rode the Greyhound bus back to Ohio, thinking to himself, “Oh, man, you’ve got to give this your all if you’re gonna have even an inkling of a chance.” He applied himself all the more diligently to his studies. “Mostly I was a self-motivating kind of individual, just trying to survive and stay in art school.”

Mitchell achieved his first professional fine-art success back in Florida during his first summer home from college. Zoltan Bush, a Hungarian immigrant and political refugee, saw his work and offered him a show at his Bay Art & Frame in Panama City, almost 90 miles away. “I rode the bus there, and people were lined up for three blocks to buy my work for $20 or $25 apiece,” Mitchell says.

Mitchell graduated in 1980 and, like many talented realist artists leaving college then and now, was recruited and hired by Hallmark Cards in Kansas City. Gradually, he began to supplement his income by entering art competitions, in which he often won top prizes—$2,000 from a show in London, another $1,500 from one in New York, another $2,000 from the National Watercolor Society. As his reputation grew, a local publication in Kansas City featured him in an article. Hallmark, he says, wanted him to stop entering shows. In November 1983, they let him go.

Depressed by this turn of fortune and by the tiny apartment he was forced to move into as a result, Mitchell found the situation worsen when he learned that his beloved grandmother had died. “I was just a mess,” he says.

Then, one morning while languishing in bed, a soft voice seemed to drift into his head—his grandmother’s voice. And he clearly heard her say, “Baby, ain’t nobody gonna give you anything in this world. You’ve gotta work for what you want.”Mitchell pauses while telling the story, still moved by the memory more than three decades later. Then he succinctly continues: “And I’ve been working hard ever since.”

He pulled himself out of bed and headed straight to a bookstore, buying himself a copy of the annual Artist’s Marketguidebook and another guide for small-scale investors. Soon he found a greeting-card company looking for freelance artists, “and they commissioned so many cards from me that I was making money like crazy.” He gained commercial illustration clients as well, including 7 Up and Budweiser.

- Dean Mitchell, Tobacco Barn Shadows, watercolor, 22 x 30.

- Dean Mitchell, Rustic West, watercolor, 10 x 15.

- Dean Mitchell, New Orleans Roof Tops, acrylic, 20 x 30.

- Dean Mitchell, Desert Light, acrylic, 16 x 20.

- Dean Mitchell, Carolyn, acrylic, 5 x 7.

- Dean Mitchell, Urban America, acrylic, 11 x 16.

Meanwhile, Mitchell began entering fine-art shows as well, though he felt uncertain about whether his race would negatively influence his chances. His solution? “I didn’t go to the openings, so they didn’t know what color I was.” Soon, he was earning $30,00 to $40,000 a year on his winnings. Success led, in turn, to the first national magazine article about him.

Then one morning in 1990, he got a call notifying him he’d been nominated for the prestigious Hubbard Art Award for Excellence, an annual $250,000 purchase prize at the Museum of the Horse in Ruidoso, NM. He flew to El Paso and drove north to Ruidoso for the black-tie awards event, and found himself rubbing shoulders with the likes of contemporary greats like Jamie Wyeth and Howard Terpning. Though Terpning won the big prize that year, while Mitchell came in sixth place, the Hubbards themselves personally paid $25,000 for his entry, ROWENA, an oil painting of an elderly black western settler.

Since that time, Mitchell has continued to earn prestigious recognition. He’s the only black artist to win the American Watercolor Society’s Gold Medal twice in its 150-year history, most recently in 2015. Just a few of his many other accolades include the Thomas Moran Award from the Salmagundi Club, the Best of Show Award three years running in the Mississippi Watercolor Society Grand National Competition, the William E. Weiss Purchase Award at the 2014 Buffalo Bill Art Show & Sale, the Donald Teague Memorial and Robert Lougheed Memorial awards at the 2014 Prix de West Invitational, and the Autry Museum Award for Watercolor at the Masters of the American West show, which he’s won a staggering eight times.

Mitchell now lives and works in Tampa, FL, with a studio in the Channelside district about a mile from the Harbour Island home he shares with his wife Connie and their 9-year-old fraternal twins. Despite his impressive success, he still relentlessly holds true to an artistic vision that has never bowed to commercial expectations. “I like my work to have commentary and to create discussions about the plight of people. I want people to look at my work and think not that it’s typical or obvious or romantic, but that it’s real, that it enlightens them and reminds them that life is fragile. If people are just looking for nice, pretty pictures, I’m not the guy.”

Meanwhile, despite the personal challenges he overcame through talent and hard work, Mitchell adamantly resists one label. “I didn’t tailor my work around being a black artist,” he states. “I tailored it around being an American artist who’s trying to capture the human condition. I’m not talking about being black. I’m talking about being a human being.”

representation

Dean Mitchell’s Marie Brooks Gallery, Quincy, FL; Mac-Gryder Gallery, New Orleans, LA; Astoria Fine Art, Jackson, WY; Cutter & Cutter Fine Art Galleries, St. Augustine, FL; E&S Gallery, Louisville, KY; Hearne Fine Art, Little Rock, AR; J. Willott Gallery, Palm Desert, CA; The Red Piano Art Gallery, Bluffton, SC; www.deanmitchellstudio.com.

- Dean Mitchell, Shanghai Alley, watercolor, 15 x 10.

- Dean Mitchell, Osage House, watercolor, 15 x 10.

- Dean Mitchell, Little House in New Mexico, acrylic, 11 x 14.

Read Original Article here.