Dean Mitchell is highly regarded as one of America’s greatest watercolourists. His reputation hinges largely on his superb craftsmanship, the emotional depth of his work, his avoidance of facile sentimentality, and an accomplished sense of formal design. Proficient in a wide range of media, including egg tempera, oil, and pastel, Mitchell engages with Black identity by drawing his subjects mainly from African-American culture.

Read more: https://www.omenkaonline.com/dean-mitchells-affirmation-projection-black-identity/

BY OLIVER ENWONWU

April 09, 2019

in ART, INTERVIEW

1 Comment

In this sixth part of our continuing series on artists in the diaspora who promote Black identity and pride through their work, we present American painter Dean Mitchell. Other artists presented in this series include Portuguese painter and designer Mario Henrique and Canadian artist Tim Okamura.

Dean Mitchell is highly regarded as one of America’s greatest watercolourists. His reputation hinges largely on his superb craftsmanship, the emotional depth of his work, his avoidance of facile sentimentality, and an accomplished sense of formal design. Proficient in a wide range of media, including egg tempera, oil, and pastel, Mitchell engages with Black identity by drawing his subjects mainly from African-American culture.

Mitchell was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1957 and grew up in Quincy, Florida. He received his formal training at the Columbus College of Art and Design in Ohio. Since gaining recognition in the 1990s with the Hubbard Art Award for Excellence, Mitchell has gone on to win several major competitions and prizes. These include the grand prize for the 1999 Arts for the Parks juried competition with his painting French Quarter Coachman and two gold medals at the Annual International Exhibition of the American Watercolor Society.

He is represented in many prestigious collections, including those of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Mississippi Museum of Art, and Canton Museum of Art. In this interview with Omenka, he discusses his work and early beginnings, as well as his larger purpose.

Figuration, landscapes, and still life occupy a significant part of your oeuvre. What is the connecting thread between them?

The connections are linked to not only our history and the spaces we occupy, but the way they inform us as full human beings. They say much about our existence, and through these mechanisms we preserve our way of life and pass on important information for developing new ideas. These ideas are linked to how we feel about our own existence in relation to the physical world. They can either enhance us mentally and spiritually, or they can be used as propaganda. The difficulty comes in creating art that comprises one’s lust for fame.

Though you are proficient in other media, such as egg tempera, oil, and pastels, you have achieved much recognition for your watercolours. Please elaborate on your creative process and on why watercolour is your preferred medium.

Watercolour is a capricious medium, and I love it because it leaves very little room for error and requires total concentration. It became my preferred medium, first, out of curiosity, and second, as an avenue for building financial stability, because by then I had become aware that mainstream society was unwilling to pay an artist of colour with equal skill to those of whites. But if I could master a medium with ultimate perfection, with skill and social content, it would propel my work into mainstream America and build an audience for my efforts. I also became aware of a number of competitive exhibitions for the medium. This allowed for enormous opportunities for exposure without anyone knowing I was an artist of colour. My work was judged entirely on merit. I had to consider that I was poor, and the only way I could remain a painter was to outwork other artists to establish my market. I never compromised my vision. Integrity and quality are paramount.

Often very well known to you, your sitters (mainly elderly) are captured with utmost sensitivity. What informs the selection of your models, particularly their physical traits?

I was raised by my grandmother. She was the backbone of our family, especially when it came to education. She believed that education is the only thing that can truly free your mind to be a critical thinker of the information put before you. She was always saying, “They can pay you less and even take your job, but an education can never be taken from you.” I have always had the utmost respect for the hard-working people of the rural town in the South that I grew up in. I also experienced the death of my great-grandmother at a young age. This taught me much about the brevity of life, how fleeting and fragile it is. I like selecting lives that I know have been lived to the fullest of their abilities. Their eyes, body language, and conversations pull me into a deeper awareness. There is also the fact that we’ve become such a youth-driven society.

With the depiction of middle and lower class people and of regions in the American South, your work may be described as an affirmation and projection of Black identity. When did you come to realise the importance of correcting imbalances in the historical representation of Black people?

Artists are observers of life, and it is natural that I would first gravitate to the space which I occupy. The neighbourhoods I was raised in were segregated. Most of my teachers were Black. Churches I attended were Black, so it is natural for me as an artist to create works that reflect my own personal experience. This is what it is to be human. In this lies the real conflict in growing up in a Euro-centric Western environment, where our images have been vilified, stereotyped, and dismantled. As a result, we have not been looked upon as full human beings. Television was the first place I became aware of the lack of respectable, powerful representation. While in college, my first museum experience taught me that we were totally invisible. They showed nothing of us. My mother had warned me that a Black man could not possibly make a living selling pictures in America. I questioned her concerns until my first encounter at the museum, walking through room after room and not seeing any image that looked like me. They did not value the Black artist’s contributions to the art world. This is a psychological castration. In spite of it, artists of colour continue to create and offer hope for the next generation.

With so many awards, features in respected publications, and exhibitions in America’s most prestigious museums, you are considered one of the greatest watercolourists working today. What would you say have been the defining moments of your career?

At the age of 23, I entered the T.H. Saunders Watercolour Competition in London, England. I won the top prize of $2,000. I had very few resources and had spent most of my savings to enter the show, so it was huge financially and a confidence builder. Certainly, becoming a member of the American Watercolor Society at the age of 27, and receiving the gold medal twice, and being the only artist of colour to do so in its 150-year history were defining moments.

The Hubbard Art Award for Excellence in 1990 was also significant because it was an invitational show and included some of the top artists in the country working in the genre of realism. My work was hanging alongside artists like Jamie Wyeth and others. The top prize was $250,000. There were about 50 artists invited and, again, I was one of the youngest and the only artist of colour. My submissions included a portrait of an elderly friend titled Rowena. Works initially were offered for sale. No one out of the 800-plus people was interested in purchasing my painting. They kept saying, “It’s beautiful, but I don’t know where I’d put her.” My mother, who accompanied me to the show, was floored when she saw the price of Jamie Wyeth’s work. His small watercolour commanded $200,000 and his oil painting commanded $500,000. She asked me if he was dead. I said, “No, he is very much alive.”

Later that evening at the sponsors’ home, Mrs Hubbard and her husband made a conscious decision to purchase my painting for $25,000, the most I had ever sold a work for. The most interesting part of this story is that no one had any idea who would win the top award. There were only six finalists, and I was one of them. Though I did not win the award, my work received the biggest applause from the audience. Yet no one had the courage to purchase the painting, other than the sponsors themselves. After the award was presented to the winning artist, Howard Terpning, Mrs Hubbard said to me, “You got a bigger applause than Howard, and he is loved here in the West. Won’t that make news?” Within moments of that conversation with Mrs Hubbard, collectors ran over to pay twice as much for my painting, to which Mrs Hubbard commented that it was no longer for sale. I became aware of the power of wealth and its impact on lending credibility, no matter how excellent the work.

Historically, accomplished artists like Rembrandt and Van Gogh have documented their changing facial features and confronted their mortality by creating multiple self-portraits over time. You seem not to have followed this path, why is this?

Quite frankly, I have never been concerned with my own mortality. Although I have painted three self-portraits over my lifetime, they had nothing to do with mortality. They had to do with anxiety and fear and isolation.

Where do the similarities between your work and earlier Afro-American artists like Henry Tanner, Andrew Wyeth, and Charles White end?

This is an interesting question. I don’t know where my work ends with artists whose work is created out of love and deep compassion for humanity. This is the link I have with them, but my experience and roads travelled are different. I’m still growing as an artist, and the work is shifting between abstraction and realism. Each artist is a product of his own time and challenges. What makes any artist’s work different is his personal journey and his creative solution to bring the world to a deeper understanding of our humanity. What separates us is our experiences, not technique or style.

Shapes, subtle colour transitions, value contrasts, form and, importantly, emotive content are characteristic elements of your works and imbue them with their power. Today, many of these features are absent from mainstream contemporary art. What can be done to encourage the revival of a fine painting tradition?

We are in an era where artists are reflecting back to what we have become. We are driven by the new, the challenging, and the entertaining, regardless of quality. There are many studies which confirm that the human attention span is not what it used to be. So many factors compete for our attention. Museums are grappling with finding an audience and new supporters. This tradition will stay alive if artists refuse to compromise quality, content, and modern-day concerns that affect all of us, regardless of race, colour, creed, religion, or background. We are all drawn to a deeper truth, regardless of the medium that is used.

What new projects are you embarking upon?

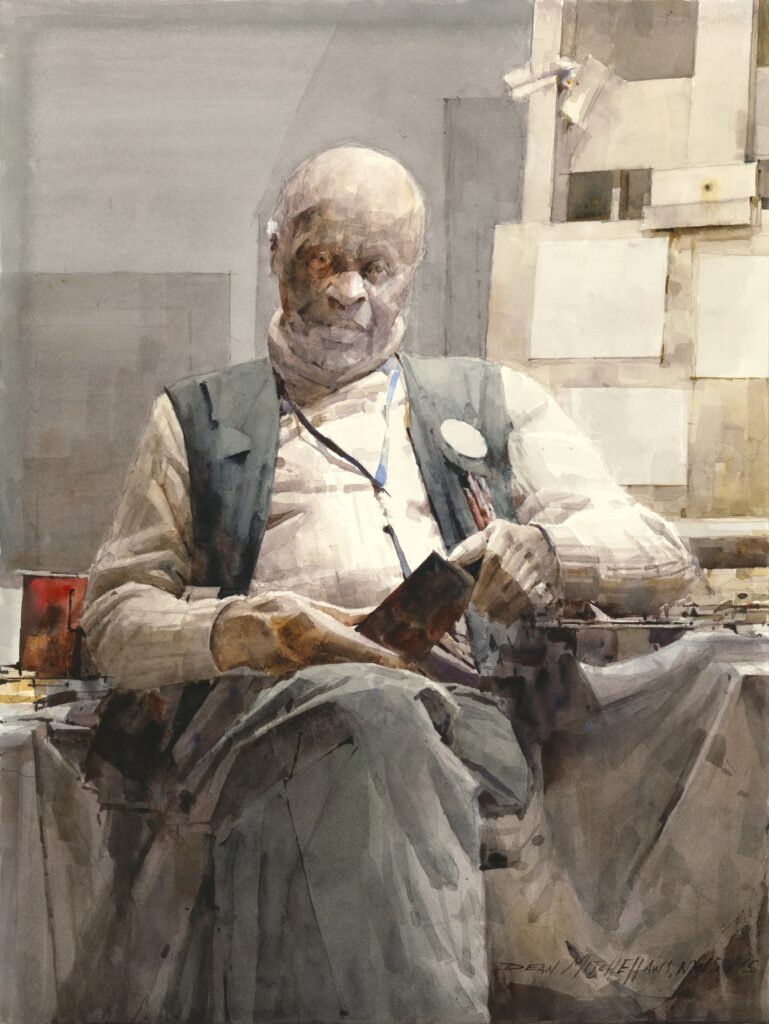

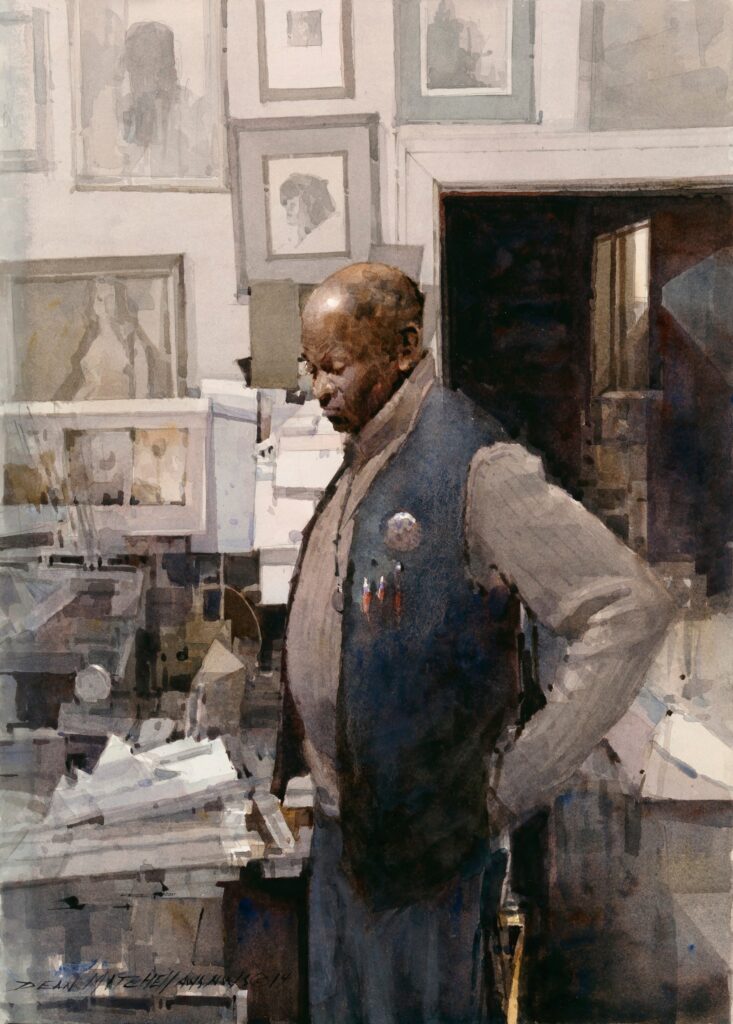

I’m working on a series of paintings of my mother, who has dementia. Also, I just opened my own gallery in my home town of Quincy, Florida, to encourage young talents in an impoverished area, to show young people how art affects our daily existence. Twilight, 2018, acrylic, 18.75x25cm

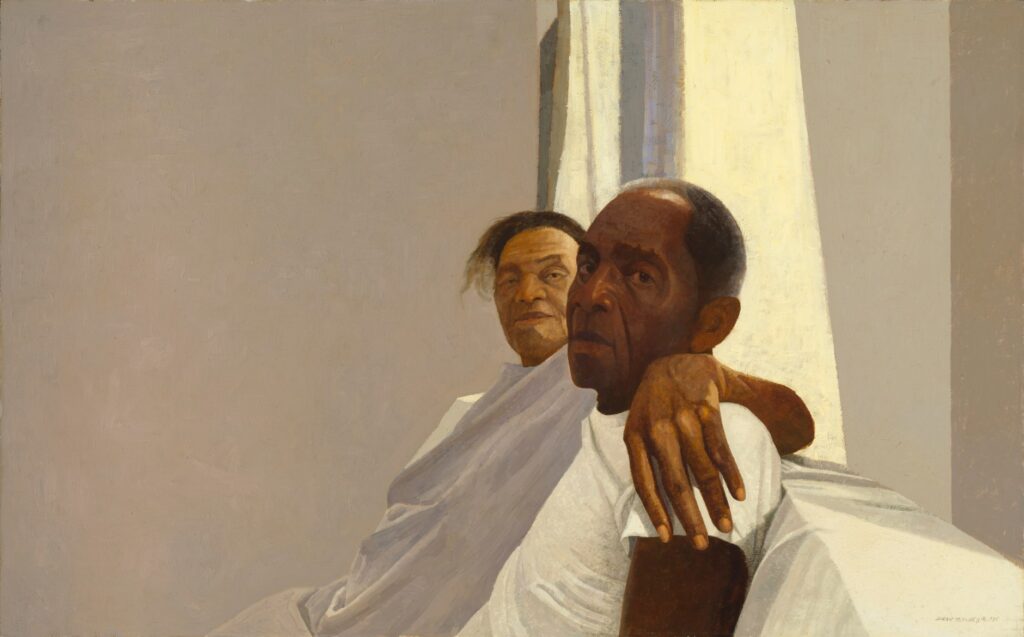

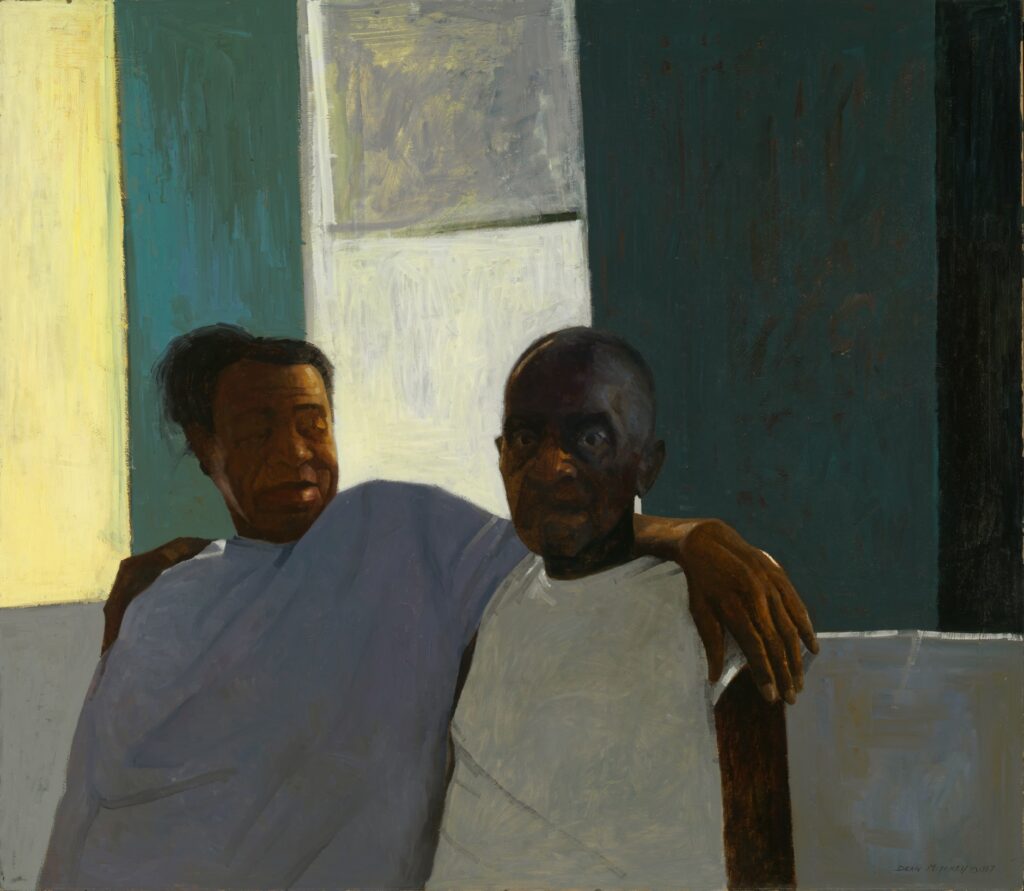

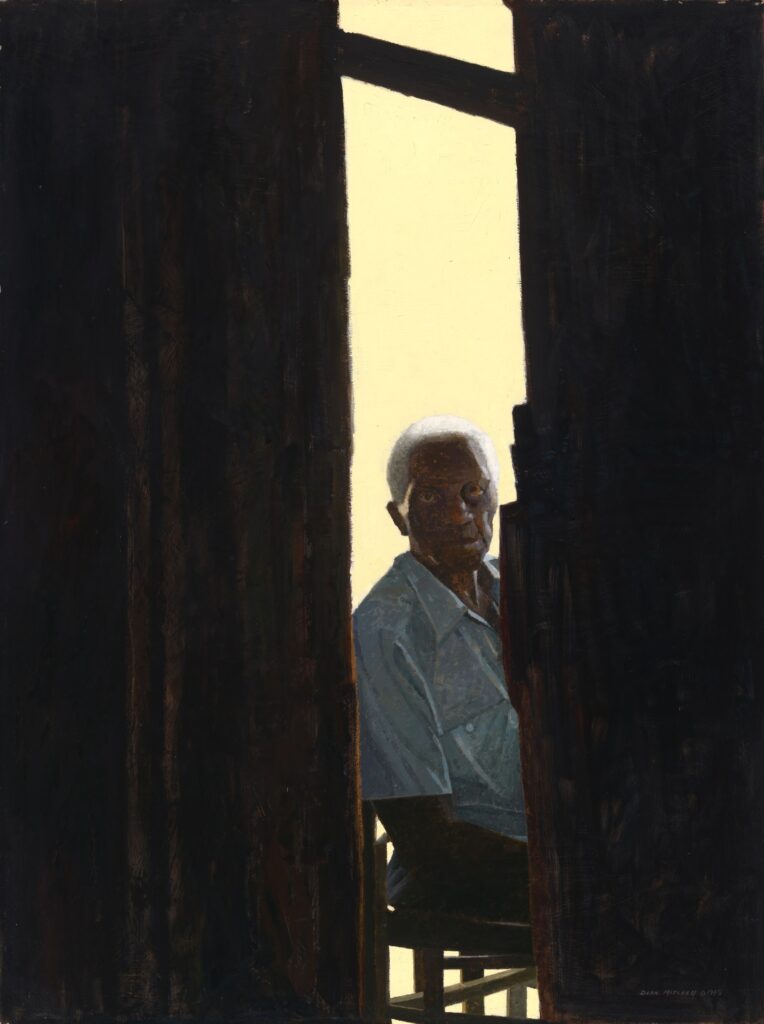

Twilight, 2018, acrylic, 18.75x25cm Against the Wall, 2000, oil, 75x100cm

Against the Wall, 2000, oil, 75x100cm